Purple peyote seedlings - a sign of extreme conditions

A purple colored epidermis is a common stress indicator for a number of cacti - stress caused either by cold or draught - and consequently can be seen as a sign of extreme growing conditions.

The peyote seedlings in the above photo haven’t seen a drop of water since late August/early September, i.e. they have been without water for almost half a year. And the last time I checked, the temperature in the coldhouse where the seedlings grow had been as low as -10C (14F). Extreme conditions for peyote seedlings indeed! And the explanation for their purple hue.

The plants are grown from seed originating from El Oso, Coahuila, Mexico. Given the locality and the seedlings’ ability to endure extreme cold and dry conditions I expect them to be Lophophora williamsii var. echinata.

Speaking of purple Lophophora williamsii var. echinata the below photo was posted a while ago by Keeper Trout. The picture shows a patch of mature peyote turned purple by the cold. According to Trout, the area in Texas where the plants grow had experienced a "hundred year freeze" including three days where the highest temperature measured at a nearby locality was 10F (less than -12C).

Purple peyote in habitat in Texas

The frost in western Texas killed off a lot of things considered freeze-hardy - including the dead peyote pictured below. This plant was from a different population than the purple patch pictured above and might have seen slightly colder temperatures, but still it’s a good indication that the freezing temperatures these plants experienced are at the limit of what Lophophora williamsii var. echinata will stand.

Dead peyote in habitat in Texas

As mentioned at the beginning of this post a purple tinted epidermis is a common sign of stress in many cacti. Another example from my coldhouse is the purplish-hued Ariocarpus retusus pictured below.

Purple tinted Ariocarpus retusus (SB 310; Cuesta la Muralla, Coahuila)

The mature peyote photos are courtesy of Keeper Trout and the Cactus Conservation Institute and originate from this post on The Corroboree.

Thursday, February 21, 2013

Peyote purple from extreme cold

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Help save and understand the peyote

The Cactus Conservation Institute (CCI) is working to obtain a scientific understanding of the biological and ecological requirements of the cactus species peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and star cactus (Astrophytum asterias), as well as gaining the community support needed to acquire and maintain a large enough tract of land in the South Texas habitat in order to ensure that both of these plants have a permanent and protected sanctuary.

If you want to support their important work it is now possible to make donations via the CCI PayPal account:

@

cactusconservation.org

You can read more details about supporting the CCI at their contributions page, and learn how they are going to spend your money at the scientific research program page. PayPal allows donations to be made in almost any currency and all contributions help - you can also support the CCI by spreading the word on internet forums and boards, blog posts or via mail. Donations are tax deductible for US citizens.

The Cactus Conservation Institute homepage

The Cactus Conservation Institute's president and co-founder Dr. Martin Terry holds the required DEA and Texas Department of Public Safety registrations to conduct research on peyote - vouching for serious (and legal) research. Martin Terry's PhD dissertation, A tale of two cacti: studies in Astrophytum asterias and Lophophora williamsii, is an interesting read and gives an understanding of the work done by the CCI.

The CCI mission statement reads:

The CCI is dedicated to the study and preservation of vulnerable cacti in their natural range – starting with peyote and star cactus. To accomplish this vision the latest techniques are being applied to understand these vulnerable hunted species, from their DNA up. All interests are being respected: the regulatory agencies, the Native American Church, the ranchers, as well as the scientific community.

I have to elaborate a bit on the "save the peyote" subject line. Peyote is not designated as endangered and not in need of being saved per se, but (to put it in the words of the CCI) "peyote is endangered at the local population level in those areas where peyoteros have access and harvest too frequently. On large ranches where peyote is adequately protected by the landowners or is remote enough from road access, it tends to be less hard pressed."

For the record, I'm not affiliated with the CCI, just an avid supporter ;-)

Wednesday, June 03, 2009

Peyote harvest regrowth – observations after one year

The Cactus Conservation Institute recently published the data from the first twelve months of their study on how harvesting affects regrowth and mortality of peyote plants in habitat in South Texas.

Untouched peyote plant (#154) from the control group

The study follows the post-harvest development of an initial group of 50 transected plants (harvested, tagged and measured March 13, 2008), a control group of 50 untouched plants, plus an additional group of 20 transected peyote plants (harvested, tagged and measured November 23, 2008). The control group is used for estimating how much “background noise” natural mortality, not associated with harvesting, contributes to the data.

Mortality of a harvested plant is inferred if it produces no regrowth of buttons. After 8 months the figure for mortality attributable to harvesting was 5/39, or about 13% (11 out of the original 50 numbered tags and the plants to which they referred had gone missing and were excluded from the study). After one year the same number of harvested study plants were located (but interestingly it was not entirely the same plants and tags as were located after 8 months). This combined with the fact that some of the buttons that showed no regrowth after 8 months have grown new pups at the one year “census” means that the harvesting mortality rate now is down to 3/39, or about 7.7%, for the initial group of study plants.

Harvested peyote plant (#128) growing 3 new pups

When harvested properly young crowns (“pups”) regenerate by lateral branching from the upper edge of the subterranean stem of the decapitated peyote plant.

Harvested peyote plant (#147) growing 4 new pups

To make up for losses in the original group of 50 harvested plants an additional group of 20 plants were harvested during the November 2008 monitoring. Unfortunately all but one of these plants show no signs of regrowth – and the one plant showing regrowth is doing so from the apical meristem, not from a subterranean areole (the crown must have been removed with a high cut, leaving the apical meristem to grow in the stem of the living plant). The devastatingly bad regrowth numbers for this group of plants is explained by a period of severe drought that followed the harvest, lasting throughout winter and into the spring.

If you want to learn more about this fascinating study check out the complete data from the peyote harvest regrowth study.

All photos in this post are used with the kind permission of the Cactus Conservation Institute. The original pictures can be found here, here, and here.

Monday, April 06, 2009

Peyote harvest regrowth

In 2008 the Cactus Conservation Institute launched a four-year study on the effects of harvesting on regrowth and mortality of peyote in habitat in South Texas.

50 plants were transected (harvested March 13, 2008) and tagged, and follow-up data were collected eight months later (November 22-23, 2008). Mortality of a harvested plant is inferred if it produces no regrowth of buttons - after 8 months 5 of the 50 plants had not grown any new pups (coming surveys will provide a more certain estimate of post-harvest mortality). Interestingly 11 out of the original 50 numbered tags and the plants to which they referred had gone missing – maybe washed down by rains, maybe dug up and buried by feral hogs. The 11 plants where neither plant nor tag were found are, at present, eliminated from the study resulting in a preliminary figure for mortality attributable to harvesting of 5/39, or about 13%.

20 more plants were harvested, measured and tagged on November 23, 2008, bringing the total number of plants in the “harvested” group up to 59. Furthermore a control group of 50 plants were also tagged and measured on November 23, 2008 – these plants will be used to indicate the magnitude of natural mortality not associated with harvesting in the future.

The surviving plants show good regrowth which is attributed to the benefit of the good harvesting practice of cutting high (at or above the junction of green aerial stem and the beige subterranean stem) and relatively level.

You can read an update on the results in the “Peyote harvest regrowth – observations after one year” post and find the complete data from the peyote harvest regrowth study here.

Saturday, January 31, 2009

Peyote conservation, trade, harvest and re-growth

A while ago professor Martin Terry, a botanist at Sul Ross University in Alpine, Texas and the authority on Lophophora, appeared on the Cultural Baggage radio show talking about the peyote cactus. Below you find excerpts from the transcript of this very informative radio program.

Asked by the interviewer, Dean Becker, if it is fair to say that the US peyote populations are becoming almost extinct professor Terry replied:

You’re heading in the right direction but I’d like to make a couple of tweaks in the way the situation is described. It’s basically, peyote is not considered an endangered species, yet. It’s a very patchy situation. In other words, on those large ranches with ten foot fences around them to keep deer in, trophy deer, which is their main business and to keep people out, on those ranches where there’s no harvesting going on of the peyote, the populations are quite healthy.

There’s plenty of peyote there and they’re nice mature adults but once you get outside of that subset of large protected ranches then you find, everywhere where the licensed peyote distributors have access, there the populations are being hammered. And it’s essentially a problem of too frequent collecting to maintain sustainability.

Dean Becker: Kind of like the way they’re getting all the fish out of the ocean.

Professor Terry: Very much so. They’re just going back to harvest before adequate reproduction and growth has replaced those ones that they harvested last time. That’s a very good analogy, the one to the over-harvesting of the oceans.

Terry then goes on to discuss who are allowed to legally harvest peyote:

There are three DEA registered distributors of peyote who have a license, which they pay a license fee for, to send their people out to harvest peyote which then, they will sell to members of the Native American Church who have their papers to show that they’re bona-fide Native Americans who are going to use the peyote in their religious ceremonies.

But that’s not the only way that peyote gets harvested. There’s nothing in the laws to prevent a duly registered Native American tribe member, member of the church, to make a contract with a landowner directly so that, in that situation, the licensed distributors are not involved. That never gets accounted for and we have to assume that’s a sizable number of peyote plants that get harvested that way. And that never gets accounted for in the official statistics on peyote numbers and peyote sales.

Terry also elaborates on the growing scarcity of land areas accessible to peyoteros and other harvesters and the effect it has on the availability and price of peyote:

[...] there’s been a change in land tenure over the past few decades. Whereas if you looked at the people who owned most of the land, say in the 1950s, you would have found that most of the people who owned the land were actually living on the land and were making a living from ranching. That is no longer the case. Now much of the land in South Texas, at least the larger tracts, are owned by people who have the money to afford such tracts now, which means they’re not living in South Texas.

They’re living in Houston, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio where the money is made. Their primary interest is to use these tracts for the hunting of trophy deer. And that’s how they make any income, any real income that they make. Cattle would be only for the tax exemption. The people like that are not going to be at all interested in allowing unknown people to be coming onto their land to harvest the peyote there for a few hundred dollars a year. I mean, that’s absurd. That’s totally uninteresting to the new landowners.

[...] if you look at what’s been happening to the [peyote] sales over the last twenty years, and these are public figures, they are readily available, you see that the number of peyote buttons harvested by the distributors and their agents has fluctuated over the last twenty years.

It went up over two million buttons a year during, let’s say the early 1990s, and then came down again. And now it’s as low as it’s been historically. It’s down right around a million and a half buttons per year but the price, the total sales in dollars for those million and half buttons, it’s just under $500,000. So that comes out to, yeah, a little over thirty cents a button.

Peyote is still too cheap when acquired through legal channels and that’s one of the problems when you get to the field because the guys who go out to harvest for the licensed distributors, they’re just interested in beer money and they will harvest these things in a willy-nilly way, not taking care at all because what are they going to get?

They’re maybe get ten or fifteen cents when they sell the buttons to the licensed distributor who ‘employs’ them. And so they don’t have anything invested in taking care of the peyote crop. It’s cheap, it’s just beer money, they want to harvest them as fast as they can, sell them and go buy their beer.

Dean Becker: Yeah. The point being that if it’s done carefully, leaving the root, that the plant can in fact grow back, right?

Professor Terry: It can indeed. Now, to what extent that happens is a very live question. If you talk to people who have a vested interest in the peyote trade then they’ll say ‘Oh yeah, you cut the top off and in two years you’ve got another harvestable plant.’ That’s a gross exaggeration. You cut the top off and, first of all, you don’t know what percentage of the plants are actually going to survive that decapitation. And it’s weather dependent.

If people come along and harvest a ranch and leave the cut tops exposed and then you have this big rain you can get a lot of infection in those plants and they’ll just die. They’re not going to produce anything ever again. So that’s one factor.

On the re-growth side, even those that do re-grow I dare say, from what I can gather as a botanist, you’re not likely to see a harvestable button until about five years after the first harvest. So that re-growth, two things are happening. First of all, they’re going to be smaller stems that grow back from the once harvested plant and secondly, it’s going to take a long time for them to get to harvestable size.

And the fact that people are coming back after two years to re-harvest again they’ve got to be harvesting buttons that are much smaller than the average adult size. And this is one of the things that you see in that marketplace. You see that there’s been a constant decrease in the size of buttons, certainly, over the past ten to fifteen years.

And so now, even though the price hasn’t gone up dramatically, it’s gone up sort of linearly and quite slowly, but if you figure in the fact that the buttons that are costing thirty cents apiece are perhaps one fifth to one tenth of the weight of what the buttons used to be at, say, when they were ten cents apiece...the price has gone up astronomically.

Dean Becker and Martin Terry discuss several other interesting issues including proposals for supplying the Native American Church with sufficient amounts of peyote. These proposals range from increasing the rate of peyote production in situ (by fertilizing natural populations) over greenhouse cultivation to whether the importation of peyote from Mexico is a feasible solution to the problems of the Native American Church of North America (Terry says no, it would basically just extend the problem with over-harvesting from Texas into Mexico).

You can read the full transcript at the Drug Truth Network or download the radio show (13.3 MB).

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

Pictographs record peyote use of earliest Texans

There is well-documented archaeological evidence indicating prehistoric peyote use, including pictographs and ancient peyote specimens found in caves and rock shelters in the lower Pecos River region of Texas. Anthropologist and archaeologist Dr. Carolyn E. Boyd has argued that the Lower Pecos pictographs provide the earliest record of peyotism.

The above picture is Carolyn Boyd's rendering of the murals at the White Shaman site. The original rock art panel is high on a bluff overlooking the Pecos River. According to Boyd it depicts the hunt for sacred peyote, a powerful medicinal and sacramental plant. She also interprets it as a ritual re-enactment of the first pilgrimage that led to the birth of gods, the establishment of the seasons and the creation of the cosmos.

The following snippet of text is taken from a recent article on the pictographs at the Mystic Shelter site.

Boyd thinks these murals were inspired by visions the people experienced during trances brought on by the hallucinogen peyote. Some depict a warrior's journey to the "Otherworld." Some describe the hunt for the sacred peyote cactus and how the cosmos was put into place.

"The rock art panels are pictorial narratives of mytho-historical events - like putting the Old Testament creation story or Passover rituals into a visual format rather than textual," Boyd says.

The artists were hunter-gatherers, and lived in an extremely arid environment where deer were prized. Yet they used valuable fat from deer bones to make paint, illustrating the importance of the artwork in their culture, Boyd says. The murals - explosions of orange, red, yellow and black - would have jumped out from the daily landscape of brown, green and gray.

"It must have been spectacular," she says. "Can you imagine the impact that would have?

The record is still in the rock.

Surviving murals are found in rock shelters throughout the Lower Pecos region, where they were protected from rain, sun and wind. According to radiocarbon dating, most, including the ones at Mystic Shelter, were made 2,950 to 4,200 years ago. More sites are still being discovered.

If you (like me;-) dream of having a closer look at the pictographs the Shumla School arranges rock art field trips allowing you to examine the incredible imagery at first hand.

Shumla School participants investigating the pictographs at Mystic Shelter, one of Texas's best sites for prehistoric art.

References

Carolyn E. Boyd, J. Philip Bering (1996), “Medicinal and hallucinogenic plants identified in the sediments and pictographs of the Lower Pecos, Texas Archaic”, Antiquity 70, 256-275

Pictographs, petroglyphs on rocks record beliefs of earliest Texans (austin360.com)

Shumla School

Rock Art Gallery

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Mescaline on the Mexican Border

There seems to be an increased focus on the alarming Texas peyote situation. A couple of weeks ago the Houston Press published a mournful, in-depth article on the vanishing peyote populations and the implications to the Native American Church.

The inside of a peyote button tastes like a dirty raw potato, with a jalapeño backbite

The article features interviews with two (out of three remaining!) peyoteros, Mauro Morales and Salvador Johnson, describing their increasing problems in finding peyote due to root-plowing, over-collection and fencing of land for hunting.

"There's some medicine, right there," he [Mauro Morales] says. It's a lone peyote button, about an inch in diameter, way too small to harvest. It'll be another five years before this peyote is mature. As he navigates the hostile flora, he points to three more small peyote plants, all of them too young to cut.

"I used to collect as much in a week as I now do in a month," he says. "I don't know what's going to happen to the medicine."

Morales almost never utters the word "peyote." For him, the small green-gray cactus is a sacrament with miraculous healing powers, hence his word for it: medicine.

What makes peyote different from just about any other cactus in the world is that it naturally produces mescaline, a psychedelic alkaloid that can induce hallucinations lasting for days.

Cactus stickers and the occasional rattlesnake are all in a day's work for Mauro Morales when he goes hunting for peyote

Salvador Johnson used to be a full-time peyotero, but guiding hunting trips pays better these days

To protect against poachers getting in and deer getting out ranchers are increasingly fencing and patrolling their grounds. The ranchers' hands-off policy represents a dilemma for Martin Terry, the world's leading authority on peyote. On the one hand, protection against peyoteros will conserve the cactus. On the other, it prevents Indians from getting access to their sacred plant.

"From the point of view of the plant, the only threat is overharvesting," he says. "The fences and personnel that protect ranch lands from would-be harvesters are the very opposite of a threat, as the protected populations of peyote inside those fences are the only healthy ones in South Texas."

Still, Terry is sensitive to the peyoteros and their way of life. He considers Mauro Morales a personal friend. He wants to make sure that Indians have access to their cactus, but that's getting harder and harder.

The whole situation seems more and more like a gordian knot in dire need of a bold solution. The available natural peyote populations in Texas are over-harvested and not given time to replenish. At the same time many NAC members are opposed to cultivating the plant. One possible solution could be to import peyote from Mexico where the plants are still plentiful; but that might at the same time export the peyote conservation crises!

You can read more on the Texas peyote situation in these posts: The “Peyote Gardens” of South Texas: a conservation crisis?, Troubled times for Texas peyote harvesters, and In Deep South Texas, peyote harvest dwindling.

The full Houston Press article and related videos are available here: Mescaline on the Mexican Border, Video: Two Peyoteros on the Mexican Border, Video: Peyote, Breakfast of Champions, and Video: Peyote in Real de Catorce

Saturday, January 19, 2008

The “Peyote Gardens” of South Texas: a conservation crisis?

In last month’s post on the troubled Texan peyoteros I referred to Anderson’s article on the peyote situation in Texas. Given the importance of this work, I saw it fit to bring it here in its full length - unfortunately I only have an old scan of the article, so the photos are a bit muddled but here goes...

The "Peyote Gardens" of South Texas: a conservation crisis?

The "Peyote Gardens" of South Texas: a conservation crisis?Cactus & Succulent Journal 67(2): 67-73 (1995)

Edward F. Anderson

Desert Botanical Garden,

1201 N. Galvin Parkway,

Phoenix, AZ 85008

More than a quarter of a million Native Americans use the peyote cactus (Lophophora williamsii) (Fig. 1) as a sacrament in a Pan-Native American religion called the Native American Church. This bona fide religion includes Native Americans from throughout the United States and Canada. Almost all of the peyote consumed in their ceremonies comes from the "peyote gardens" on the Mustang Plains in south Texas, which has been carefully documented by Morgan (1976, 1983) and by Morgan and Stewart (1984). Federal and Texas laws permit the collecting and use of peyote by Native Americans in their religious ceremonies.

Fig. 1 - Peyote (Lophophora williamsii) in habitat on Las Islas Ranch, Starr County, Texas.

The origins of the Native American Church are complex, and the reader can refer to detailed accounts of how the modern peyote religion arose in the late nineteenth century through the influences of traditional Native American ceremonies and Christianity in both Mexico and the United States (Anderson, 1980; Stewart, 1989). This paper describes the long relationship of Hispanic "peyoteros" in south Texas and members of the Native American Church, as well as the impact of many years of collecting peyote tops or "buttons" within the Tamaulipan Thorn Shrub vegetation. Many report that the peyote populations are greatly diminished in size (Morgan and Stewart, 1984; Jerry Patchen, pers. comm.; Salvador Johnson, pers. comm.; Jackie Poole, pers. comm.). Is the continued collecting of the plant for religious purposes leading to a serious conservation problem? Will peyote continue to be available to Native Americans in the foreseeable future?

I recently had the opportunity to return to south Texas, where I had collected and studied peyote populations more than 30 years ago. I met Hispanic peyoteros, visited their drying sites, and talked with leaders of the Native American Church. I also examined a peyote site, where plants had reportedly been harvested about five years earlier.

Peyote has a broad distribution throughout most of northern Mexico and across the Rio Grande into Texas (Anderson, 1980). Though peyote occurs in west Texas near Big Bend National Park, the most extensive area within the U.S. is from the mouth of the Pecos River southward and eastward nearly to Brownsville. The main area in which peyote has been harvested commercially is within Starr, Jim Hogg, Webb, and Zapata counties, primarily along the western Bordas Escarpment, the Aguilares Plain, and the Breaks of the Rio Grande (Morgan and Stewart, 1984). Over 90% of this land is privately owned and well-fenced.

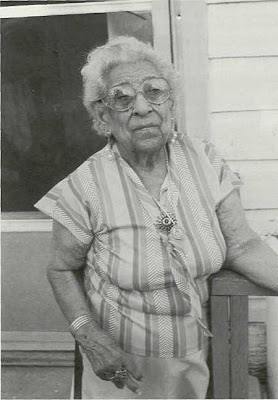

Fig. 2 - Amada Cardenas, an Hispanic peyotero, who has collected peyote for Native Americans since 1933.

Hispanic peyoteros and some Native Americans have harvested peyote within this region for more than 100 years. Until the 1960's the main area for collecting the plant was in the more northern part, mostly in Webb County in the vicinity of Mirando City. In fact, the first peyoteros worked out of a small community just to the south of Mirando City called Los Ojuelos. Abandoned many years ago, the small town is now being rebuilt. Hispanic peyoteros and Native Americans developed a strong relationship, which has persisted to the present. The home of Amada Cardenas (Fig. 2), who is the oldest living peyotero, is located at the edge of Mirando City. It has become an important religious site for Native Americans who visit the area, with peyote meetings held in either a hogan or tipi. Amada, now 90 years old, was born in Los Ojuelos and became a peyotero in 1933. She is known to most Native Americans as "Mom"; often she provides Road Chiefs (church leaders) with especially fine specimens of peyote (Fig. 3) to serve as "Father Peyote" in the ceremonies they lead. Peyote growing in her garden is also highly revered (Fig. 4). She and the other peyoteros in the northern part of peyote country primarily sell dried peyote. More recently, peyoteros have operated in the more southern area around Rio Grande City; they deal mainly in fresh or "green" peyote, but dry some as well.

Fig. 3 - Especially large, fine peyote tops, which will be used as "Father Peyotes" in religious ceremonies of the Native American Church.

Fig. 4 - Peyote growing in the garden of Amada Cardenas. Note the coins and corn-husk cigarette butts that have been left as "offerings."

Peyoteros must be licensed by the Texas Department of Public Safety and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the federal government, paying annual fees of $5 and $400, respectively (Salvador Johnson pers. comm.; Jerry Patchen, pers. comm.). They must keep accurate records of how many pieces of peyote they harvest and sell each year. Responsible peyoteros lease the rights to collect peyote from the land owners, a typical lease costing $800-1000 for permission to work on a small ranch for 30 days (Salvador Johnson, pers. comm.). Leases for ranches of several thousand acres would cost far more. Unfortunately, a few peyoteros fail to secure permission to collect on private land, thus causing land owners to become angry because of their trespassing. Illegal trespassing was a particularly bad problem in the 1960's and 1970's when non-Native American "hippies" or members of the drug cult came to south Texas to search for peyote. They would often camp illegally and have extended drug parties on private property. Their illegal trespassing, coupled with their association with more serious drugs, caused many ranchers to close their lands to everyone, including peyoteros and members of the Native American Church. These "hippies" have not returned in recent years.

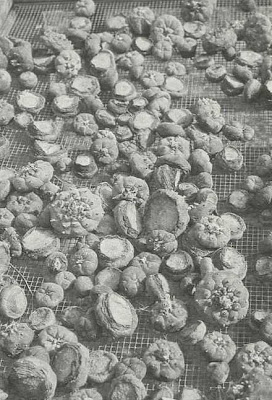

Fig. 5 - Salvador Johnson, who has been a peyotero for more than 30 years, with drying peyote "buttons."

There are currently 11 peyoteros working in south Texas. Each harvests and sells about 200,000 tops a year (Salvador Johnson, pers. comm.). However, productivity varies from individual to individual, as well as the season of the year. For example, no one collects during Texas's hunting season, for it is far too dangerous to wander through the brush harvesting plants, with hunters searching through the thick brush for the numerous white-tailed deer. One peyotero, Salvador Johnson of Mirando City (Fig. 5), has been in the business for more than 30 years. He works throughout the northern region of the cactus's distribution in south Texas, an area of 200,000 to 300,000 acres, and collects more than 300,000 buttons or tops a year. He claims that he and four other workers can collect about 30,000 heads on 25 acres of land in about 5 hours — if the plants are abundant. It takes 10 days to dry the buttons (Fig. 6), for which he charges 15-17 cents a piece. The size of the buttons makes no difference with regard to price, for both state and federal laws are concerned only in the number of pieces collected and sold. Thus, Salvador is able to charge $ 150-170 per 1000 dried buttons, plus $5.00 per 1000 for shipping. The price for dried peyote has steadily risen. In 1966 the cost was $15 per 1000 buttons, but it had risen to $80 per 1000 by 1981 (Morgan and Stewart, 1984). Thus, the price has doubled in the last 10 years.

Fig. 6 - Freshly harvested peyote tops that are being dried for sale to Native Americans.

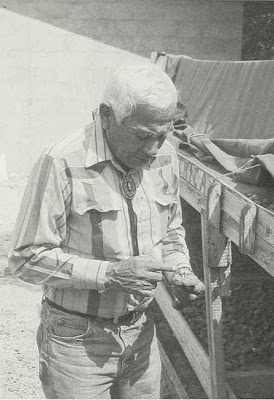

Anthony Davis, also known as White Thunder (Fig. 7), is an 83-year-old Pawnee Road Chief and President of The Native American Church of the United States in Texas. Anthony, a longtime member of the Church, says (pers. comm.) that the annual demand by all branches of the Native American Church in the U.S. and Canada for peyote "buttons" is 5-10 million. Unfortunately, the peyoteros of south Texas come far short of reaching this need. If they were to harvest that many tops, what would be the longterm effects on the natural populations? In fact, what is the impact of their present collecting of about two million tops each year?

Fig. 7 - Anthony Davis, a Pawnee Road Chief, examining drying peyote "buttons."

I visited a population of peyote on Las Islas Ranch in northern Starr County. The ranch is presently closed to outsiders, including peyoteros, with numerous high fences and locked gates. The area we visited had never been root-plowed and consisted of natural vegetation (Fig. 8), with heavy stands of mesquite and other native shrubs. No peyoteros have been on the property in more than three years. I examined numerous plants and found about half had been previously harvested. The usual technique for harvesting is to use a flat, short-handled shovel or machete, which is carefully pushed just beneath the soil to sever the top of the plant from the tuberous root system. If the top is removed at ground level, regeneration is rapid, usually with one - or more - heads arising from the original root system (Figs. 9, 10). New tops will sprout in less than two months if the plant is in a state of active growth. The Las Islas site had many peyote plants with one or more small heads, most less than 5 centimeters (2 inches) in diameter. Several large individuals were found growing under large mesquite trees. Peyote seems to be remarkably resilient if proper harvesting techniques are practiced by peyoteros.

Fig. 8 - Natural habitat of peyote on Las Islas Ranch, Starr County, Texas.

Fig. 9 - Cluster of small peyote tops.

Fig. 10 - Soil removed to show that the tops arise from a large root system from which a top had been removed several years earlier.

What is the future of peyote harvesting in south Texas? The long-term prognosis, if present conditions continue to exist, is grim. Interestingly, the most serious threat to peyote is not its harvest by peyoteros. They are actually good conservationists and have a responsible approach to their livelihood. They want to carefully nurture the wild populations so that they will have a steady income. Members of the Native American Church, in turn, are dependent upon the peyoteros, for there is no other legal supply of their sacrament. Some will travel to south Texas to collect their own plants, but most cannot afford the time or expense.

The two most serious threats to a continued supply of peyote are root-plowing (Fig. 11) and the locking up of ranches to the peyoteros. These two activities by the land owners are understandable, because they want to make their land economically productive, as well as to protect themselves from lawsuits. The brushland has many snakes and other dangers, and in this time of litigation many owners fear the possibility of lawsuits if anyone is injured or killed on their property. Hunting has become a significant source of income for many ranchers, with groups of hunters paying for permission to be on the land during the winter hunting season. The property has therefore been closed in order to propagate game, prevent poaching, and insure that only those who have paid are on the property. Elaborate, high fences have been built to restrict the movement of deer.

Fig. 11 - Root-plow (note man standing beside it), with Opuntia engelmannii in the foreground and the newly cleared area behind.

In recent years ever-larger numbers of Native Americans are coming to visit the "peyote gardens," which are almost totally on private land that is fenced and posted. Some Native Americans resent being prohibited from visiting sites where their most important "medicine" grows, thus creating serious tensions between them and the ranchers.

Root-plowing is the only means whereby a land owner can prepare land for cattle grazing, after which various grasses are planted. Of course, native plants are virtually all destroyed, with the

exception of Opuntia engelmannii (Fig. 11). It multiplies rapidly by vegetative means once the ground is disturbed and in many places it forms nearly impenetrable thickets.

As more and more land is subjected to rootplows or is locked up, there is an ever-increasing pressure on those remaining populations of peyote that are legally accessible. An area of peyote should not be recut for at least five years, but often peyoteros cannot wait that long if the demand for buttons is great. Thus, smaller and smaller tops are harvested (Fig. 12) at ever-higher prices.

Fig. 12 - Very small peyote "buttons," indicating that peyoteros are being forced to harvest regenerated tops before they have grown to a sufficient size. Photos by author.

There appear to be three ways to alleviate the probable shortage of peyote within the near future. None is easy, and none may be possible.

First, efforts should be made to persuade ranch owners to allow peyoteros to legally have the right to harvest peyote on their property through leases or permits. Landowners of Texas feel strongly that their lands are private. Negotiations would be difficult, but if some ranchers would allow carefully supervised harvesting, then perhaps others would follow. Unfortunately, the image of peyote as a drug rather than a sacred medicine is hard to dispel. This is an unfortunate consequence of the drug culture and their coming to Texas to collect and consume peyote.

Second, negotiations could be initiated with the Mexican and U.S. governments to allow the importation of dried peyote from Mexico where the supply is still plentiful. This would provide income for Mexican harvesters, with U.S. Hispanics serving as importers and distributors. However, at present Mexico has laws which are even more restrictive regarding possession and use of peyote than in the U.S. Perhaps the new NAFTA treaty and the greater interest of both governments to work cooperatively may at least provide the possibility of discussions about peyote.

Third, salvage operations could be undertaken with the cooperation of ranchers who are rootplowing fields. If they could be pursuaded to allow peyoteros to collect entire peyote plants prior to their destruction by the plow, then those collected could be placed into cultivation. Suitable fields with security would have to be found, but such an activity would provide income to the rancher, to the harvester, and to the grower. The plant grows well in cultivation, though few peyoteros and Native Americans have been inclined to propagate other than small back yard gardens of peyote, thinking that the wild populations will never be depleted. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

Peyote is not a dangerous drug that victimizes Native Americans as alcohol has done. Rather, it is a sacred plant having a history of use of more than 6000 years. It is only used ceremonially and as medicine. It is not addicting, nor does it cause harmful effects. It is one of the most important medicines to Native Americans. Their religion, in which peyote is used as the sacrament, is highly moral and serious. For anyone who has experienced the night-long ceremony of singing, praying, and mediating, there can be only respect and admiration. Serious efforts must be made to assure the continued supply of peyote for members of the Native American Church.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this investigation was provided by the CSSA Research Fund. It is much appreciated. In addition, I wish to thank Dr. Stacy Schaefer of The University of Texas-Pan American for arranging travel, accommodations, and interviews in south Texas. I also want to thank Jerry Patchen for several valuable suggestions in the writing of this paper.

References

Anderson, E. F. 1980. Peyote: the divine cactus. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Morgan, G. R. 1976. Man, plant, and religion: peyote trade on the mustang plains of Texas. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Colorado.

Morgan, G. R. 1983. The biogeography of peyote in south Texas. Bot. Mus. Leafl., Harvard Univ. 29:73-86.

Morgan, G. R., and O. C. Stewart. 1984. Peyote trade in south Texas. Southwest. Hist. Quart. 87:269-296.

Stewart, O. C. 1989. The peyote religion: a history. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Thursday, December 20, 2007

Troubled times for Texas peyote harvesters

Ted Anderson’s article The “Peyote Gardens” of South Texas: a conservation crisis? (1995) documented that the Texan peyote populations have greatly diminished in size, and that a conservation crisis might be imminent as wild populations are depleted by over-harvesting and habitat destruction.

A recent Reuters article sums up the current grim situation for the Texan peyoteros and the “peyote gardens” they harvest. Today only 3 peyoteros are active in Texas, compared to as many as 27 peyote dealers being licensed in the 1970s; the 2006 harvest yielded 1.6 million peyote buttons - a dramatic decline from the mid-1990s peaks of around 2.3 million buttons.

A recent Reuters article sums up the current grim situation for the Texan peyoteros and the “peyote gardens” they harvest. Today only 3 peyoteros are active in Texas, compared to as many as 27 peyote dealers being licensed in the 1970s; the 2006 harvest yielded 1.6 million peyote buttons - a dramatic decline from the mid-1990s peaks of around 2.3 million buttons.

Peyoteros are licensed by the government to harvest and sell peyote to members of the Native American Church - an occupation that seems oddly disconnected from the rest of the U.S. fighting its war on drugs for decades.

"There's still some peyote out there, but not like there used to be. It's getting kind of scary now," said Morales [one of the remaining peyoteros] above the crowing of a rooster from the roof of his shed.

He has had his peyotero license for 16 years, and before that worked as a picker, walking the arid brush country of southern Texas with a machete in hand and lopping off the top of the cactus when he found it.

It used to be easy -- peyote was plentiful and landowners were happy to let peyoteros harvest the cactus for a small fee.

But urban development and widespread "root plowing," which scrapes natural vegetation off the land to replace it with grass for cattle grazing, destroyed many of the peyote fields that once sprawled along the U.S.-Mexico border.

And more and more peyote land is off-limits because it is being bought by rich Texans who turn it into hunting preserves, said Martin Terry, a biology professor at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas.

Consequently the available peyote populations are over-harvested, resulting in less peyote of an inferior quality. Terry suggests the US Drug Enforcement Administration to allow greenhouse cultivation of peyote as a solution to the current situation (tongue-in-cheek described as “a serious case of over-grazing by human herbivores” ;-). Cultivated peyote would secure ample supplies for the Native American Church and spare the remaining wild peyote populations.

It should be noted that Martin Terry is one of the few scientists currently conducting peyote related research, including investigations of proper peyote harvesting techniques.

You can read the full Reuters article, Texan deals peyote legally, here.

As an aside I have to mention that the Brisbane Times features the same article under the headline Growing psychedelic drugs aint what it used to be... a good illustration of the saying “everything is in the eye of the beholder” ;-)

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

In Deep South Texas, peyote harvest dwindling

I’m aware that this Seattle Times article has been available on the net for some time; but I think it fits well with the theme intoned by the posts on proper peyote harvesting techniques and the Huichol peyote pilgrimage, so here goes...

In Deep South Texas, peyote harvest dwindling

By Sylvia Moreno (2005)

Salvador Johnson is one of four licensed peyote distributors left in the United States. He has harvested the plant for 47 years.

MIRANDO CITY, Texas — In the heart of Rio Grande brush country, Salvador Johnson works a patch of land just east of the Mexican border that is sacred to Native Americans.

Spade in hand, eyes scanning the earth as he pushes through the spiny brush, Johnson searches the ground carefully. “This is good terrain for peyote,” he says. “There’s a low hill — the rain starts on top and goes down to water this — and there’s a lot of brown ground.”

He stops, points the tip of his shovel at a 3-inch spot of green that barely crests the soil under a clump of blackbrush and announces: “This is what you look for. You look for something that is not ordinary on the terrain. I saw that green.”

One of the last remaining “peyoteros,” Johnson, 58, has been harvesting the small round plant in and around this tiny community for 47 years — long before the hallucinogenic Lophophora williamsii cactus was classified as a narcotic and outlawed by federal and state governments. Then as now, it is for use by Native Americans as the main sacrament in their religious ceremonies.

Johnson is part of a nearly extinct trade of licensed peyote harvesters and distributors, at a time when the supply of the cactus and access to it is dwindling. The plant grows wild only in portions of four southern Texas counties and in the northern Mexico desert just across the Rio Grande.

But some Texas ranch owners have stopped leasing land to peyoteros and now offer their property to deer hunters or oil and gas companies for considerably higher profits. Others have plowed under peyote, and still others have never opened their land.

On the ranchland that is worked by peyoteros, conservationists are concerned about the overharvesting of immature plants as the Native American population and demand for the cactus grows.

“Will there be peyote for my children and my children’s children?” asked Adam Nez, 35, a Navajo who had driven 26 hours with his father-in-law from their reservation in Page, Ariz., to stock up on peyote at Johnson’s home.

That question and possible solutions to the problem — such as trying to legalize the importation of peyote from Mexico, and creating legal cultivation centers in the United States — are being studied by members of the Native American Church, Indian rights advocates and conservationists.

There are an estimated 200,000 to 500,000 members of the church in the United States. Although 90 percent of the peyote in North America grows in Mexico, the number of ceremonial users there — mostly Huichol Indians — is a small fraction of the number in the United States and Canada.

“In effect, you have a whole continent grazing on little pieces of south Texas,” said Martin Terry, a botany professor at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas, who specializes in the study of peyote.

The church was incorporated in 1918 in Oklahoma to protect the religious use of peyote by indigenous Americans. Its charter was eventually expanded to other states, and in 1965, a federal regulation was approved to protect the ceremonial use of peyote by Indians. In 1978, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

But subsequent conflicts between federal policy and state drug laws precipitated the passage of a federal law in 1994 to guarantee the legal use, possession and transportation of peyote “by an Indian for bona fide traditional ceremonial purposes in connection with the practice of a traditional Indian religion.”

The law extends protection against prosecution for the possession and use of peyote only to members of federally recognized tribes.

“Over the last 40 years, there have been lots of equal-protection defenses to criminal prosecution thrown up, with people saying ‘my use of this controlled substance is religiously derived,’ ” said Steve Moore, a senior staff attorney with the Native American Rights Fund.

Though not considered addictive, peyote is included in the Drug Enforcement Agency’s list of Schedule I controlled substances along with heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana and methaqualone.

Although the DEA acknowledges the importance of the hallucinogenic cactus to the religious rites of Native American peyote users, the agency says the drug has a high potential for abuse and has no accepted medicinal purpose in the United States.

The Texas Department of Public Safety has licensed peyote distributors since the mid-1970s, when the number in the state peaked at 27. It dwindled to four last year. State records show that only three distributors have harvested and sold peyote so far this year.

For the past five years, an average of almost 1.9 million peyote buttons have been sold annually, according to state records.

References

Sylvia Moreno, “In Deep South Texas, peyote harvest dwindling”, Seattle Times

Monday, December 04, 2006

Proper peyote harvesting technique

Lophophora williamsii (peyote) populations have diminished in large areas of South Texas where peyoteros harvest the cactus for ceremonial use by the Native American Church. Habitat destruction caused by urban development, rootplowing, etc., account for much of the reduction, but the regulated commercial harvest of peyote is also taking its toll. Some harvesters cut the peyote too low (it can be very hard to tell where the shoot ends and the root begin) - consequently many of the decapitated plants will not regenerate new stems and are left to die.

To address this problem Martin Terry and James D. Mauseth have investigated the proper technique for harvesting peyote, and found that the cactus must be cut off at or immediately below its base, leaving the subterranean portion of the plant (including all or most of the subterranean part of the stem) in the ground to regenerate new crowns. Their harvesting technique is outlined below.

Plant about to be cut transversely at the base of the crown (the photosynthetic part of the stem), i.e., at ground level.

Plant about to be cut transversely at the base of the crown (the photosynthetic part of the stem), i.e., at ground level.

Cut has been made parallel to the ground surface, and the harvested crown (below) has been removed from the subterranean portion of the stem (above, remaining in the ground). The cut surface shows a cross section of the vascular cylinder (ring of yellow tissue near center of stem), the pith within the vascular cylinder, and the yellowish green parenchymal tissue of the cortex of the stem (between vascular ring and epidermis).

Cut has been made parallel to the ground surface, and the harvested crown (below) has been removed from the subterranean portion of the stem (above, remaining in the ground). The cut surface shows a cross section of the vascular cylinder (ring of yellow tissue near center of stem), the pith within the vascular cylinder, and the yellowish green parenchymal tissue of the cortex of the stem (between vascular ring and epidermis).

The underside of the harvested crown (left) shows a very narrow (2–3 mm wide) ring of bark at the perimeter of the cut surface, indicating that the cut was barely below the base of the crown, in the uppermost portion of subterranean stem. The cut surfaces match, except that crown parenchyma (left) is slightly greener due to higher chlorophyll content, whereas the subterranean stem parenchyma (right) is more yellowish.

The underside of the harvested crown (left) shows a very narrow (2–3 mm wide) ring of bark at the perimeter of the cut surface, indicating that the cut was barely below the base of the crown, in the uppermost portion of subterranean stem. The cut surfaces match, except that crown parenchyma (left) is slightly greener due to higher chlorophyll content, whereas the subterranean stem parenchyma (right) is more yellowish.

Two young peyote crowns (“pups”) regenerating by lateral branching from the upper edge of the subterranean stem of a plant that was decapitated 7.5 months previously. This plant is the same individual shown in the 3 previous pictures. Each of the new crowns is ca. 1.5 cm in diameter.

Two young peyote crowns (“pups”) regenerating by lateral branching from the upper edge of the subterranean stem of a plant that was decapitated 7.5 months previously. This plant is the same individual shown in the 3 previous pictures. Each of the new crowns is ca. 1.5 cm in diameter.

If the peyote is cut too deep no tubercles are left to sprout and continue growing after the top has been removed, i.e. the closer to soil level the plant is cut, the greater the chances are that the remaining parts of the plant will retain healthy tubercles and be able to re-grow new crowns. Terry and Mauseth base their technique on detailed studies of the anatomy of root, shoot and hypocotyl (region between shoot and root) and also give recommendations on how to distinguish shoots from roots without actually cutting the plant open.

References

Martin Terry, James D. Mauseth (2006), “Root-shoot anatomy and post-harvest vegetative clonal development in Lophophora williamsii (Cactaceae: Cacteae): implications for conservation”, Sida, Contributions to Botany 22, 565-592

(Download the article from Sida - 19.2 MB)

Sylvia Moreno, “In Deep South Texas, peyote harvest dwindling”, Seattle Times

See also How to sustainably harvest Lophophora williamsii (Peyote) from Kadas Garden.

Monday, October 23, 2006

The quest for Texan Lophophora williamsii

For a while I’ve been searching for L. williamsii seeds and plants originating from Trans-Pecos, Texas. It’s been quite hard to find any – probably because of the legal status of Lophophora williamsii in the USA. Earlier this year I finally found a retailer selling plants originating from material collected in the Pecos River area, Val Verde County, Texas (JJH 8608293), and promptly ordered a handful of plants.

Lophophora williamsii, Pecos River, Val Verde Co.

The plants have been grown very hard and are of a high quality with good, sturdy roots; the width of the plants are in the range from 1.5 to 2.25 cm (0.6-0.9''). They were reasonably priced at 4 euro (~ 5 USD) each.

I recently received a second batch that I planned to grow in an unheated cold house, but I now have second thoughts and will probably postpone the cold house experiment until I’m able to propagate the plants from seed.

The plants were bought at Kakteen Kliem, a German retailer with a good selection of plants with locality information (I also bought some of his Lophophora fricii, Parras, Coahuila, Mexico (JJH 9602115) and Astrophytum asterias, Rio Grande City, Texas (PQ 91)). I would be glad to hear of any other sources of Trans-Pecos Lophophora with detailed locality information.

Monday, March 27, 2006

Prehistoric peyote use

I’m growing my Lophophora plants for aesthetics, but I have to admit that the mescaline content and the traditional ceremonial use by Native Americans are fascinating aspects. Apparently peyote use is ancient; archaeological discoveries in caves and rock shelters in the lower Pecos River region, Texas indicate that peyote use dates thousands of years back.

Peyote buttons recovered from a rock shelter in the lower Pecos River region (photo reproduced from Boyd et al.)

Recently El-Seedi et al. subjected samples from two archaeological specimens of peyote buttons to radiocarbon dating and alkaloid analysis. The specimens were discovered in Shumla Cave No. 5 on the Rio Grande, Texas and now reside in the collection of the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Texas – see photo above. The peyote samples were dated to be in the time interval 3780–3660 BC, and the alkaloid yield was approximately 2% in both samples. The only peyote alkaloid that could be identified was mescaline, i.e. no traces of the other major peyote tetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids like lophophorine, anhalonine, pellotine, and anhalonidine could be found.

The authors conclude “From a scientific point of view, the now studied ‘mescal buttons’ appears to be the oldest plant drugs which ever yielded a major bioactive compound upon phytochemical analysis. From a cultural perspective, our identification of mescaline strengthens the evidence that native North Americans already recognized and valued the psychotropic properties of the peyote cactus 5700 years ago.”

The ancient use of peyote is also supported by Boyd et al. who argue that Lower Pecos pictographs (found in the same area as the archaeological peyote specimens) can be seen as evidence for early peyotism.

References

Hesham R. El-Seedi, Peter A.G.M. De Smet, Olof Beck, Göran Possnert, Jan G. Bruhn (2005), “Prehistoric peyote use: Alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas”, Journal of Ethnopharmacology 101, 238–242

Carolyn E. Boyd, J. Philip Bering (1996), “Medicinal and hallucinogenic plants identified in the sediments and pictographs of the Lower Pecos, Texas Archaic”, Antiquity 70, 256-75

Tuesday, December 13, 2005

Cacti of the Trans-Pecos & Adjacent Areas

I’ve meant to buy this book for more than a year now; I finally got it ordered and received my copy a couple of days ago. I haven’t read through it all yet, just browsed the sections on Ariocarpus, Epithelantha, and Lophophora. These are excellent and very informative; I’m looking forward to have the time to read the book from end to end. The Texas Tech University Press description reads: “Of the 132 species and varieties of cacti in Texas, about 104 of them occur in the nine counties of the Trans-Pecos region and in nearby areas. This volume includes full descriptions of those many genera, species, and varieties of cacti, with sixty-four maps showing the distribution of each species in the region.

The Texas Tech University Press description reads: “Of the 132 species and varieties of cacti in Texas, about 104 of them occur in the nine counties of the Trans-Pecos region and in nearby areas. This volume includes full descriptions of those many genera, species, and varieties of cacti, with sixty-four maps showing the distribution of each species in the region.

The descriptions follow the latest findings of cactus researchers worldwide and include scientific names; common names; identifying characters based on vegetative habit, flowers, fruit, and seeds; identification of flowerless specimens; and phenology and biosystematics.”

All Time Most Popular Posts

-

Lophophora williamsii (peyote) populations have diminished in large areas of South Texas where peyoteros harvest the cactus for ceremonial ...

-

On various occasions I've been asked what growing media I'm using for my cactus plants. I don't have a set soil mix recipe as su...

-

Below is a list of retailers/nurseries selling cactus seed and plants. I've only listed vendors I've done business with. If you ar...

-

Most cacti are easily grown from seed - and with a little patience and care they can be grown into beautiful plants. Lophophora williamsi...

-

In last month’s post on the troubled Texan peyoteros I referred to Anderson’s article on the peyote situation in Texas. Given the importanc...

-

Yet another slightly off topic and probably not entirely politically correct post, but I couldn’t help noticing the similarity of my monstr...

-

Flowering stand of San Pedro cacti (Trichocereus pachanoi) To me the main draw of the San Pedro cactus ( Trichocereus pachanoi (syn. Ech...

-

In the June 2008 issue of the Cactus & Co magazine Jaroslav Šnicer, Jaroslav Bohata, and Vojtěch Myšák described a new Lophophora spec...

-

There seems to be an increased focus on the alarming Texas peyote situation. A couple of weeks ago the Houston Press published a mournful, i...

-

I spent two weeks working in Delhi, India during January. I had one weekend off and had planned to spend it in Delhi at my own leisure, but ...