Ted Anderson’s article The “Peyote Gardens” of South Texas: a conservation crisis? (1995) documented that the Texan peyote populations have greatly diminished in size, and that a conservation crisis might be imminent as wild populations are depleted by over-harvesting and habitat destruction.

A recent Reuters article sums up the current grim situation for the Texan peyoteros and the “peyote gardens” they harvest. Today only 3 peyoteros are active in Texas, compared to as many as 27 peyote dealers being licensed in the 1970s; the 2006 harvest yielded 1.6 million peyote buttons - a dramatic decline from the mid-1990s peaks of around 2.3 million buttons.

A recent Reuters article sums up the current grim situation for the Texan peyoteros and the “peyote gardens” they harvest. Today only 3 peyoteros are active in Texas, compared to as many as 27 peyote dealers being licensed in the 1970s; the 2006 harvest yielded 1.6 million peyote buttons - a dramatic decline from the mid-1990s peaks of around 2.3 million buttons.

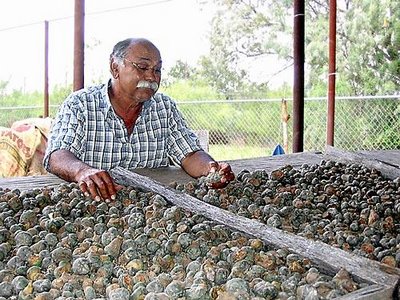

Peyoteros are licensed by the government to harvest and sell peyote to members of the Native American Church - an occupation that seems oddly disconnected from the rest of the U.S. fighting its war on drugs for decades.

"There's still some peyote out there, but not like there used to be. It's getting kind of scary now," said Morales [one of the remaining peyoteros] above the crowing of a rooster from the roof of his shed.

He has had his peyotero license for 16 years, and before that worked as a picker, walking the arid brush country of southern Texas with a machete in hand and lopping off the top of the cactus when he found it.

It used to be easy -- peyote was plentiful and landowners were happy to let peyoteros harvest the cactus for a small fee.

But urban development and widespread "root plowing," which scrapes natural vegetation off the land to replace it with grass for cattle grazing, destroyed many of the peyote fields that once sprawled along the U.S.-Mexico border.

And more and more peyote land is off-limits because it is being bought by rich Texans who turn it into hunting preserves, said Martin Terry, a biology professor at Sul Ross State University in Alpine, Texas.

Consequently the available peyote populations are over-harvested, resulting in less peyote of an inferior quality. Terry suggests the US Drug Enforcement Administration to allow greenhouse cultivation of peyote as a solution to the current situation (tongue-in-cheek described as “a serious case of over-grazing by human herbivores” ;-). Cultivated peyote would secure ample supplies for the Native American Church and spare the remaining wild peyote populations.

It should be noted that Martin Terry is one of the few scientists currently conducting peyote related research, including investigations of proper peyote harvesting techniques.

You can read the full Reuters article, Texan deals peyote legally, here.

As an aside I have to mention that the Brisbane Times features the same article under the headline Growing psychedelic drugs aint what it used to be... a good illustration of the saying “everything is in the eye of the beholder” ;-)